Explore o reservatório de teste de serviços públicos dos EUA liderado por minorias da Isle em nossa série de blogs "Histórias de sucesso".

Reshmina William, PhD (Gerente de Projetos, Isle Americas)

Reservatório de teste de concessionárias de serviços públicos da Isle, liderada por minorias nos EUA

Flint, Michigan, tornou-se um símbolo dos desafios da infraestrutura de água potável dos Estados Unidos.

Em 2014, as autoridades da cidade tomaram a decisão de economizar custos ao deixar de comprar água do Distrito de Água e Esgoto de Detroit e passar a adquiri-la do Rio Flint. Sem medidas adequadas de controle de corrosão, a nova fonte de água lixiviou chumbo, uma potente neurotoxina, das antigas linhas de serviço da cidade para os suprimentos de água potável. Dezenas de milhares de pessoas, inclusive crianças, foram expostas ao chumbo em concentrações que, às vezes, excediam cem vezes o nível de ação estabelecido pela Agência de Proteção Ambiental dos EUA (USEPA).

Mais de uma década depois, os moradores de Flint ainda estão vivendo com as consequências. Muitos desafios de saúde física e mental de longo prazo foram associadas ao desastre, incluindo depressão, transtorno de estresse pós-traumático, dificuldades de aprendizagem e transtorno de déficit de atenção e hiperatividade. A perda de confiança nos sistemas de água é tão profunda que muitos moradores de Flint ainda usam apenas água engarrafada para as necessidades básicas da casa.

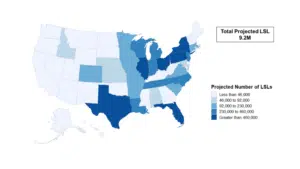

Embora Flint seja um microcosmo dos desafios enfrentados pelas comunidades carentes nos Estados Unidos, ela não é, de forma alguma, a única. A USEPA estima que existam cerca de 9,2 milhões de linhas de serviço de chumbo enterrados em cidades de todo o país, muitos em comunidades de baixa renda concentradas no Cinturão da Ferrugem, na Flórida e no Texas.

Imagem de USEPA

O problema vai além do chumbo. Quase 25% da população dos EUA é atendido por sistemas de água potável que violam a Lei da Água Potável Segura: a lei federal que supostamente garante o acesso equitativo à água potável limpa para todos os americanos. Muitas dessas violações ocorrem em comunidades que são econômica ou socialmente vulneráveis. Devido ao histórico de segregação residencial nos EUA, é mais provável que as populações de cor vivam com uma infraestrutura de água envelhecida, subdesenvolvida e com financiamento insuficiente, suscetível a violações de saúde.

Ao mesmo tempo, as pessoas de cor continuam sub-representadas nas empresas de serviços públicos que atendem suas comunidades. Os trabalhadores hispânicos e negros tendem a estar significativamente sub-representados em cargos de nível superior e melhor remunerados nas empresas de serviços públicos, como engenharia ou gerência. Em 2016, os trabalhadores negros, hispânicos e asiáticos combinados representavam apenas 15% de diretores executivos de concessionárias de água. Sem um lugar à mesa, as comunidades minoritárias lutam para que suas necessidades sejam ouvidas.

Um reservatório de teste para empresas de serviços públicos lideradas por minorias

Os serviços públicos dos EUA liderados por minorias (MLUU) Reservatório de teste nasceu de um desejo de abordar esses dois desafios relacionados. Como parte do Fórum de CEOs de serviços públicos da Isle, um grupo de CEOs está defendendo um programa para nivelar o campo de atuação para a tomada de riscos inovadores entre a liderança dos serviços públicos. Cathy Bailey, da Greater Cincinnati Water Works (GCCW), está liderando a iniciativa.

Como diretora executiva da GCCW, a mais antiga empresa de abastecimento de água do estado de Ohio, Cathy tem um longo legado a cumprir. Ao longo de suas três décadas de trabalho na GCCW, ela sempre sentiu a pressão de ser uma pessoa de cor em uma função de liderança, especialmente agora como a primeira diretora afro-americana na história da GCCW.

"O setor de água ainda é muito dominado por homens brancos", diz ela. "Isso traz muitos desafios sobre como [as minorias] são tratadas, como somos vistos e as expectativas que as pessoas às vezes têm sobre nós."

Cathy sempre esteve ciente das responsabilidades implícitas que acompanham seu cargo. "Eu sempre soube que muitos olhos estavam voltados para mim", diz ela. Muitos desses olhos não eram particularmente amigáveis, fato que a tornou muito mais avessa a riscos em seus primeiros dias de liderança. "Como uma pessoa de cor que lidera uma grande empresa de abastecimento de água, você aprende a assumir riscos com cautela."

No entanto, como Cathy sabe muito bem, o risco é uma parte inerente da inovação. "Você tem que estar disposto a colocar as coisas em prática... você tem que estar aberto a falhar". Muitos líderes minoritários de concessionárias de serviços públicos não têm o apoio de que precisam para "falhar" e, assim, promover inovações ousadas em suas concessionárias.

O MLUU amplifica as vozes das empresas de serviços públicos lideradas por minorias para que elas possam atingir suas metas de sustentabilidade e justiça ambiental. Ele fornece aos líderes de serviços públicos de minorias as proteções que lhes permitem a liberdade de inovar com ousadia no setor de água na mesma medida que seus pares. Ao mesmo tempo, o MLUU também incentiva os participantes a elevar as necessidades de sustentabilidade socioeconômica e ambiental das comunidades desfavorecidas dentro de sua área de serviço.

Além do GCCW, o MLUU estimulou o envolvimento entusiasmado de usuários finais na Carolina do Sul, Indiana, Kentucky e outros locais. À medida que a rede de testes para esse reservatório continua a se expandir, esperamos conectar comunidades carentes de todos os EUA com tecnologias que possam ajudar a atender às suas necessidades de maneiras novas e inovadoras.

Uma ferramenta para a defesa pessoal

Minha função no Trial Reservoir tem sido, de certa forma, o ápice de uma paixão pela justiça ambiental que vem de longa data. Ao longo da minha carreira acadêmica e profissional, vi os danos ambientais desproporcionais que afetam nossas populações mais vulneráveis. Vi a falta de espaços verdes resultar em inundações urbanas no South Side de Chicago e linhas de serviço de chumbo agrupadas em algumas das áreas de baixa renda de Washington, DC.

Embora tenhamos acesso a tecnologias incríveis que podem tratar, distribuir e recuperar a água melhor do que nunca, essas tecnologias geralmente não chegam às mãos daqueles que mais precisam delas. Com esse Reservatório de Teste, vejo a chance de ajudar a corrigir algumas dessas desigualdades, diminuindo a barreira à inovação e ampliando as vozes das comunidades minoritárias e desfavorecidas.

Ser gerente da Trial Reservoir me ajudou a crescer como profissional e como pessoa. Ajudei a desenvolver métricas de desempenho, coordenar a documentação e redigir comunicados à imprensa e à mídia: tarefas que me ajudaram em minhas funções como gerente de projeto. Em nível pessoal, trabalhar com o Reservatório Experimental do MLUU me deu a oportunidade de interagir com líderes de serviços públicos de minorias em todo o país, que estão trabalhando diligentemente para melhorar suas comunidades, uma gota de cada vez.

Acredito que o MLUU é uma oportunidade única de expandir nosso trabalho para comunidades que poderiam se beneficiar muito do apoio financeiro e programático que o Trial Reservoir oferece. Estou ansioso para ampliar nossos horizontes, alcançando comunidades que nunca ouviram falar do Reservatório Experimental ou da Isle. Estou ansioso para colaborar com novas categorias de usuários finais, como pequenos sistemas rurais que podem se beneficiar da utilização do Reservatório Experimental como uma ponte para oportunidades de financiamento maiores e mais lentas. Acima de tudo, estou animado para ver como o MLUU evolui para apoiar a rede de outras organizações fantásticas que já atuam nesse espaço, especialmente aquelas que trabalham diretamente com comunidades carentes.

Nem todos os desafios de igualdade ambiental podem ser resolvidos apenas com tecnologia. No entanto, espero que o MLUU possa fazer parte de um kit de ferramentas mais amplo que as comunidades desfavorecidas possam usar para se defenderem em sua luta pela justiça ambiental.

Se você estiver interessado em saber mais sobre o MLUU - ou conhecer alguém que possa estar! - entre em contato com [email protected] para obter mais informações.